7. DISEASE MANAGEMENT

7.1. Treatment of primary urethral carcinoma in males

Previously, treatment of male distal (penile urethra and fossa navicularis) urethral carcinoma followed the procedure for penile cancer, with surgical excision of the primary lesion with a wide safety margin [36]. Distal urethral tumours exhibit significantly improved survival rates compared with proximal tumours [70]. Therefore, in the treatment of distal urethral carcinoma, the focus of clinicians has shifted towards improving functional outcomes and quality of life (QoL), while preserving oncological safety. A retrospective series found no evidence of local recurrence in males with pT1-3N0-2 distal urethral carcinoma that were treated with well-defined, penile-preserving surgery and additional iliac/inguinal lymphadenectomy (LND) for clinically suspected LN disease, even with < 5mm resection margins (median follow-up: 17-37 months) [71]. Similar results for the feasibility of penile-preserving surgery have also been reported [72, 73]. However, a series on patients treated with penile-preserving surgery for distal urethral carcinoma reported a higher risk of progression in patients with positive proximal margins, which was also more frequently observed in cases with lymphovascular and peri-neural invasion of the primary tumour [74].

7.1.1. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the treatment of primary urethral carcinoma in males

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| In distal urethral tumours, performing a partial urethrectomy with a minimal safety margin does not increase the risk of local recurrence compared with penile amputation. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Offer distal urethrectomy as an alternative to penile amputation in localised distal urethral tumours if negative surgical margins can be achieved intra-operatively. | Weak |

Ensure complete circumferential assessment of the proximal urethral margin if penile- preserving surgery is intended. | Strong |

7.2. Treatment of localised primary urethral carcinoma in females

7.2.1. Urethrectomy and urethra-sparing surgery

To provide the highest chance of local cure in females with localised urethral carcinoma, primary radical urethrectomy should include removal of all the periurethral tissue from the bulbocavernosus muscle, bilaterally and distally, with a cylinder of all adjacent soft tissue up to the pubic symphysis and bladder neck. Bladder neck closure and vesicostomy, for example, by using the appendix, for primary distal urethral lesions have been shown to provide satisfactory functional results [37].

Previous series have reported outcomes in females with mainly distal urethral tumours undergoing primary treatment with urethra-sparing surgery, with or without additional radiotherapy (RT), as compared to primary urethrectomy, with the aim of maintaining integrity and function of the lower urinary tract [75,76]. In longer-term series with a median follow-up of 153-175 months, local recurrence rates in females undergoing partial urethrectomy with intra-operative frozen section analysis were 22-60%, and distal sleeve resection of > 2cm resulted in secondary urinary incontinence in 42% of patients who subsequently required additional reconstructive surgery [75, 76].

Ablative surgical techniques, i.e., transurethral resection (TUR) or laser, used for small distal urethral tumours, have also resulted in considerable local failure rates of 16%, with a CSS rate of 50%. This emphasises the critical role of local tumour control in females with distal urethral carcinoma to prevent local and systemic progression [75].

7.2.2. Radiotherapy

In females, RT was investigated in several older series with a medium follow up of 91-105 months [77]. With a median cumulative dose of 65Gy (range 40-106Gy), the five-year local control rate was 64% and seven-year CSS was 49% [77]. Most local failures (95%) occurred within the first two years after primary treatment [77]. The extent of urethral tumour involvement was found to be the only parameter independently associated with local tumour control, but the type of RT (EBRT vs. interstitial brachytherapy) was not [77]. In one study, the addition of brachytherapy to EBRT reduced the risk of local recurrence by a factor of 4.2 [78]. Of note, pelvic toxicity in those achieving local control was considerable (49%), including urethral stenosis, fistula, necrosis, cystitis and/or haemorrhage, with 30% of the reported complications graded as severe [77].

7.2.3. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the treatment of localised primary urethral carcinoma in females

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| In females with distal urethral tumours, urethra-sparing surgery and local radiotherapy represent alternatives to primary urethrectomy but are associated with increased risk of tumour recurrence and local toxicity. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Offer radical urethrectomy unless specific criteria for organ preservation are met. | Strong |

| Offer urethra-sparing surgery as an alternative to primary urethrectomy to females with distal urethral tumours if negative surgical margins can be achieved intra-operatively. | Weak |

| Offer local radiotherapy as an alternative to urethral surgery to females with localised urethral tumours but discuss local toxicity. | Weak |

7.3. Multimodal treatment in locally advanced urethral carcinoma in both males and females

7.3.1. Introduction

Multimodal therapy in PUC consists of definitive surgery plus chemotherapy with additional RT [79]. Multimodal therapy was often underutilised in locally advanced disease (only 16%), notwithstanding promising results [79-82]. In a study, monotherapy was associated with decreased local recurrence-free survival after adjusting for stage, histology, sex and year of treatment (p = 0.017). The use of monotherapy has decreased over time [83]. Treatment in academic centres was reported to result in higher utilisation of neoadjuvant- and multimodal-treatment and improved OS in patients with locally advanced urothelial and SCC PUC [68].

7.3.2. Preoperative systemic treatment

Retrospective studies reported that cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy regimens can be effective, providing prolonged survival even in LN-positive disease. Moreover, the studies emphasised the critical role of surgery after chemotherapy to achieve long-term survival in patients with locally advanced urethral carcinoma. In an analysis of males with primary UC using the National Cancer Database, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) was reported to decrease the risk of all-cause mortality, while AC was not associated with an OS benefit. As compared to no chemotherapy in males with primary UC, NAC was reported to exhibit improved OS compared with adjuvant chemotherapy [84].

In a series of 124 patients, 39 (31%) were treated with perioperative platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced PUC (12 received NAC; 6 received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; and 21 adjuvant chemotherapy). Patients who received NAC or chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced PUC (> cT3 and/or cN+) appeared to demonstrate improved survival compared to those who underwent upfront surgery with or without adjuvant chemotherapy [85]. Another retrospective series, including 44 patients with advanced PUC, reported outcomes on 21 patients who had preoperatively received cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy according to the underlying histologic subtype. The overall response rate for the various regimens was 72%, and the median OS was 32 months [51].

Recent advances in the management of MIBC, including adjuvant immunotherapy and perioperative chemo-immunotherapy, should be considered for the treatment of patients with locally advanced PUC such that if UC is the predominant histology, the EAU MIBC Guidelines [2] can be followed.

7.3.3. Chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra

The clinical feasibility of local RT with concurrent chemotherapy as an alternative to surgery in locally advanced SCC has been reported in several series. This approach offers the potential for genital preservation [86-90]. The largest retrospective series reported outcomes in 25 patients with primary locally advanced SCC of the urethra treated with two cycles of 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin C with concurrent EBRT. A complete clinical response was observed in ±80% of patients. The five-year OS and disease-specific survival was 52% and 68%, respectively. Salvage surgery, initiated only in non-responders or in cases of local failure, was not reported to be associated with improved survival [86].

A large retrospective cohort study in patients with locally advanced urethral carcinoma treated with adjuvant RT and surgery versus surgery alone demonstrated that the addition of RT improved OS [91].

7.3.4. Salvage treatment in recurrent primary urethral carcinoma after surgery for primary treatment

A multicentre study reported that patients who were treated with surgery as primary therapy and underwent surgery or RT-based salvage treatment for recurrent solitary or concomitant urethral disease demonstrated similar survival rates compared to patients who never developed recurrence after primary treatment [69].

7.3.5. Treatment of regional lymph nodes

Nodal control in urethral carcinoma can be achieved either by regional LND [36], RT [77] or chemotherapy [51]. Currently, there is still no clear evidence supporting prophylactic bilateral inguinal and/or pelvic LND in all patients with urethral carcinoma [53]. However, in patients with clinically enlarged inguinal/pelvic LNs or invasive tumours, regional LND should be considered as initial treatment, since cure might still be achievable with limited disease [36]. It has been shown that, in patients with invasive urethral SCC and cN1-2 disease, inguinal LND conferred an OS benefit [53].

7.3.6. Summary of evidence and recommendations for multimodal treatment in advanced urethral carcinoma in both males and females

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| In locally advanced urethral carcinoma, cisplatin-based chemotherapy with curative intent prior to surgery might improve survival compared to chemotherapy alone or surgery followed by chemotherapy. | 3 |

| In locally advanced SCC of the urethra, treatment with chemoradiotherapy might be an alternative to surgery. | 3 |

| In locally advanced UC and SCC of the urethra, treatment in academic centres improves OS. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Refer patients with advanced urethral carcinoma to academic centres. | Strong |

| Discuss treatment of patients with locally advanced urethral carcinoma within a multidisciplinary team of urologists, radiation oncologists, and oncologists. | Strong |

| Determine perioperative treatment according to histology in locally advanced urethral carcinoma treated with curative intent. | Weak |

| Follow the European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer for the use of perioperative systemic therapy in patients with locally advanced urethral urothelial carcinoma. | Weak |

| Offer the combination of curative radiotherapy (RT) with radiosensitising chemotherapy for definitive treatment and genital preservation in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the urethra. | Weak |

| Offer salvage surgery or RT to patients with urethral recurrence after primary treatment. | Weak |

| Offer inguinal lymph node (LN) dissection to patients with LN-positive urethral SCC when all involved inguinal LNs are macroscopically resectable. | Weak |

7.4. Treatment of urothelial carcinoma of the prostate

Local conservative treatment with extensive TUR and subsequent bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) instillation is effective in patients with Ta or Tis prostatic urethral carcinoma [92]. A systematic review reported that patients treated with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) before BCG show a better local response in the prostatic urethra with a higher disease-free survival (80-100% vs. 63-89%) and progression-free survival (PFS) (90-100% vs. 75-94%) than patients in studies in which no TURP was performed [91]. Risk of understaging local extension of prostatic urethral cancer at TUR is high in patients with ductal or stromal involvement [93]. Some earlier series have reported superior oncological results for the initial use of radical cystoprostatectomy as a primary treatment option in patients with ductal involvement [94, 95]. In 24 patients with prostatic stromal invasion treated with radical cystoprostatectomy, an LN mapping study found that 12 patients had positive LNs, with an increased proportion located above the iliac bifurcation [96].

7.4.1. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the treatment of urothelial carcinoma of the prostate

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| Patients undergoing TURP for prostatic UC prior to BCG treatment show superior complete response rates compared to those who do not. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Offer a urethra-sparing approach with transurethral resection and bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) to patients with non-invasive urethral carcinoma or carcinoma in situ of the prostatic urethra and prostatic ducts. | Strong |

| In patients not responding to BCG, or in patients with ductal or stromal involvement, perform a cystoprostatectomy with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy. | Weak |

7.5. Metastatic disease

An analysis of the SEER database reported that patients with M1 disease who underwent primary site surgery did not exhibit any survival benefit [60]. Systemic therapy in metastatic disease should be selected based on the histology of the tumour. The EAU MIBC Guidelines can be followed if UC is the predominant histology [2]. Although patients with urethral carcinoma have been included in large clinical trials on immunotherapy, no subgroup analyses of response rates have been reported to date [97].

In addition, there is an urgent clinical need to better address the role of local palliative treatment strategies in PUC, including surgery, which has been shown to positively impact QoL aspects in select patients with advanced genital cancers [98].

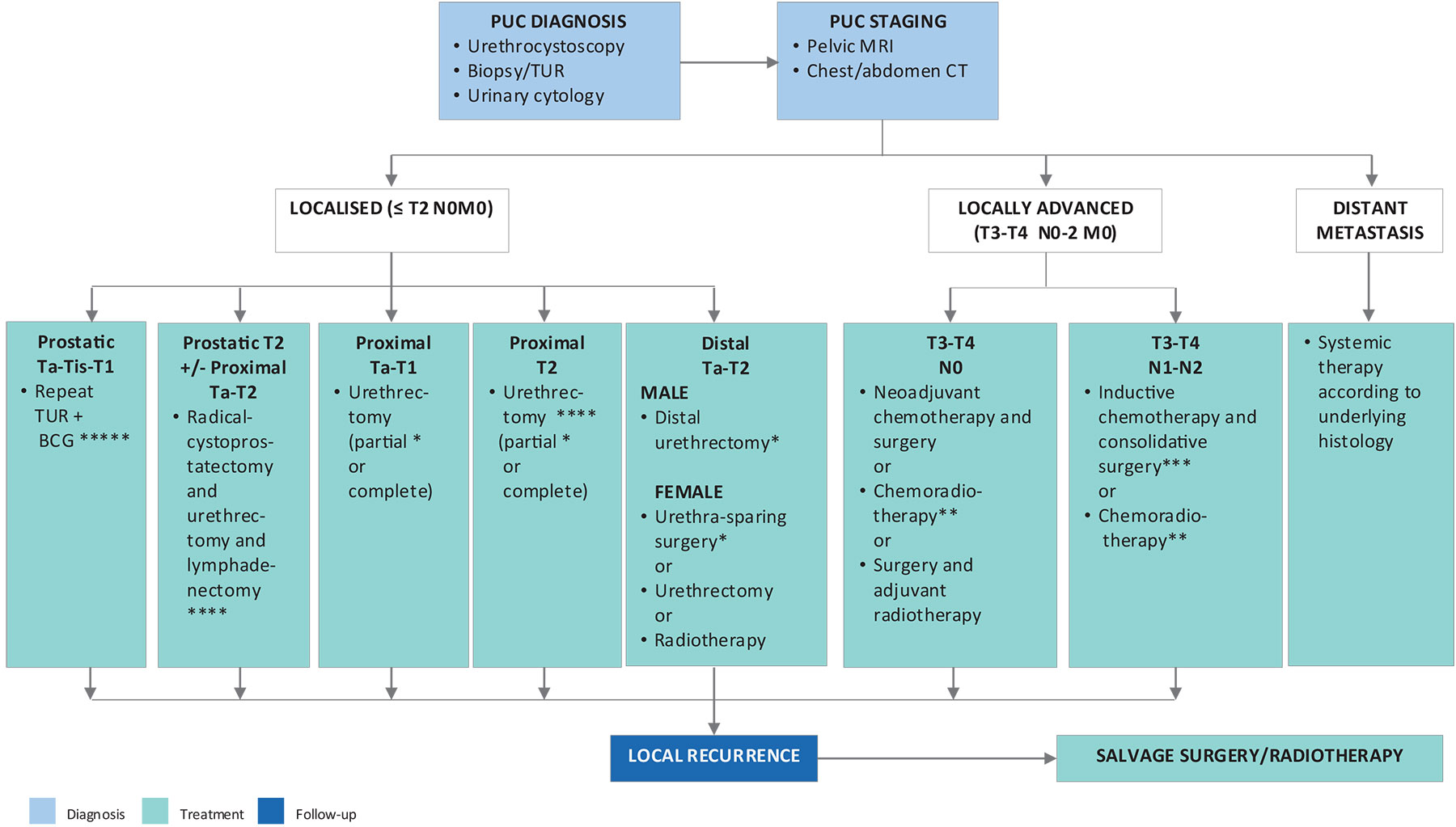

Figure 7.1: Management of primary urethral carcinoma * Ensure complete circumferential assessment if penile-preserving/urethra-sparing surgery or partial urethrectomy is intended.

* Ensure complete circumferential assessment if penile-preserving/urethra-sparing surgery or partial urethrectomy is intended.

** Squamous cell carcinoma.

*** Regional lymphadenectomy should be considered in clinically enlarged lymph nodes.

**** Consider neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

***** In BCG-unresponsive disease: consider (primary) cystoprostatectomy +/- urethrectomy + lymphadenectomy.

BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PUC = primary urethral carcinoma; TUR = transurethral resection.