6. DISORDERS OF EJACULATION

6.1. Introduction

Ejaculation is a complex physiological process that comprises emission and expulsion processes and is mediated by interwoven neurological and hormonal pathways [573]. Any interference with those pathways may cause a wide range of ejaculatory disorders. The spectrum of ejaculation disorders includes premature ejaculation (PE), retarded or delayed ejaculation, anejaculation, painful ejaculation, retrograde ejaculation, anorgasmia and haemospermia.

6.2. Premature ejaculation

6.2.1. Epidemiology

Historically, the main problem in assessing the prevalence of PE has been the lack of a universally recognised definition at the time that surveys were conducted [574]. See Section 4.2 for a comprehensive discussion of the epidemiology of PE.

6.2.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

The aetiology of PE is relatively unknown, with limited data to support suggested biological and psychological hypotheses, including anxiety [575-578], penile hypersensitivity [579-586] and 5-hydroxytryptamine (HT) receptor dysfunction [587-592]. The classification of PE into four subtypes [206] has contributed to a better delineation of lifelong, acquired, variable and subjective PE [593-595]. It has been hypothesised that the pathophysiology of lifelong PE is mediated by a complex interplay of central and peripheral serotonergic, dopaminergic, oxytocinergic, endocrinological, genetic and epigenetic factors [596]. Acquired PE may occur due to psychological problems - such as sexual performance anxiety, and psychological or relationship problems and/or co-morbidity, including ED, prostatitis, hyperthyroidism and poor sleep quality [597-600]. Variable PE is considered to be a normal variation of sexual function whereas subjective PE can stem from cultural or abnormal psychological constructs [206].

A significant proportion of men with ED also experience PE [210,601]. High levels of performance anxiety related to ED may worsen PE, with a risk of misdiagnosing PE instead of the underlying ED. According to the National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS), the prevalence of PE is not affected by age [202], unlike ED, which increases with age. Premature ejaculation is not affected by marital or income status [202,602]. However, PE is more common in Black men, Hispanic men, and men from regions where an Islamic background is common [202,603,604] and the prevalence may be higher in men with a lower educational level [202,210]. Other reported risk factors for PE include genetic predisposition [592,605-608], poor overall health status and obesity [202], prostate inflammation [609-613], hyperthyroidism [597], low prolactin levels [614], high testosterone levels [615], vitamin D and B12 deficiency [616,617], diabetes [618,619], MetS [620,621], lack of physical activity [622], emotional problems and stress [202,623,624], depressive symptoms [624], and traumatic sexual experiences [202,210].

6.2.3. Impact of PE on quality of life

Men with PE are more likely to report low satisfaction with their sexual relationship, low satisfaction with sexual intercourse, difficulty relaxing during intercourse, and less-frequent intercourse [625-627]. Premature ejaculation can have a detrimental effect on self-confidence and the relationship with the partner, and may sometimes cause mental distress, anxiety, embarrassment and depression [625,628,629]. Moreover, PE may also affect the partner’s sexual functioning and their satisfaction with the sexual relationship decreases with increasing severity of the patient’s condition [630-632]. Despite the possible serious psychological and QoL consequences of PE, few men seek treatment [203,210,633-636].

6.2.4. Classification

There is still little consensus about the definition and classification of PE [637]. It is now universally accepted that “premature ejaculation” is a broad term that includes several concepts belonging to the common category of PE. The most recent definition comes from the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision, where PE was renamed as Early Ejaculation [638]: “Male early ejaculation is characterized by ejaculation that occurs prior to or within a very short duration of the initiation of vaginal penetration or other relevant sexual stimulation, with no or little perceived control over ejaculation. The pattern of early ejaculation has occurred episodically or persistently over a period of at least several months and is associated with clinically significant distress.”

This definition includes four categories: male early ejaculation, lifelong generalised and situational, acquired generalised and situational, and unspecified. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (DSM-V) [212] and the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) [639] published definitions for lifelong and acquired PE. These definitions are overlapping, with 3 shared factors (1. Time to ejaculation assessed by IELT; 2. Perceived control; and, 3. Distress, bother, frustration, interpersonal difficulty related to the ejaculatory dysfunction), resulting in a multi-dimensional diagnosis [639].

Two more PE syndromes have been proposed [594]:

- ‘Variable PE’ is characterised by inconsistent and irregular early ejaculations, representing a normal variation in sexual performance.

- ‘Subjective PE’ is characterised by subjective perception of consistent or inconsistent rapid ejaculation during intercourse, while ejaculation latency time is in the normal range or can even last longer. It should not be regarded as a symptom or manifestation of true medical pathology [640].

6.2.5. Diagnostic evaluation

Diagnosis of PE is based on the patient’s medical and sexual history [641-644]. History should classify PE as lifelong or acquired and determine whether PE is situational (under specific circumstances or with a specific partner) or consistent. Special attention should be given to the duration time of ejaculation, degree of sexual stimulus, impact on sexual activity and QoL, and drug use or abuse. It is also important to distinguish PE from ED. Many patients with ED develop secondary PE caused by the anxiety associated with difficulty in attaining and maintaining an erection [601,645]. Furthermore, some patients are unaware that loss of erection after ejaculation is normal and may erroneously complain of ED, while the actual problem is PE [636].

6.2.5.1. Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT)

Although it has been suggested as an objective diagnostic criterion and treatment outcome measure [646,647], the use of IELT alone is not sufficient to define PE, as there is significant overlap between men with and without PE [648,649]. Moreover, some men may experience PE in their non-coital sexual activities (e.g., during masturbation, oral sex or anal intercourse); thus, measuring IELT will not be suitable for their assessment. Although PE is apparently less prevalent and less bothersome among men who have sex with men (MSM) [650], many of them may also suffer from PE and IELT cannot be applied to them [651,652]. Although some studies demonstrated that MSM report longer ejaculation latency time compared to straight men [650], some others failed to demonstrate such a difference [653].

In everyday clinical practice, self-estimated IELT is sufficient [654]. Self-estimated and stopwatch-measured IELT are interchangeable and correctly assign PE status with 80% sensitivity and 80% specificity [655].

Measurement of IELT with a calibrated stopwatch is mandatory in clinical trials. For any drug treatment study of PE, Waldinger et al. suggested using geometric mean instead of arithmetic mean IELT because the distributed IELT data are skewed. Otherwise, any treatment-related ejaculation delay may be overestimated if the arithmetic mean IELT is used instead of the geometric mean IELT [656].

6.2.5.2. Premature ejaculation assessment questionnaires

The need to objectively assess PE has led to the development of several questionnaires based on using PROMs. Only two questionnaires can discriminate between patients who have PE and those who do not:

- Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (PEDT): A five-item questionnaire based on focus groups and interviews from the USA, Germany, and Spain assesses control, frequency, minimal stimulation, distress and interpersonal difficulty [657]. A total score of > 11 suggests a diagnosis of PE, 9 or 10 suggests a probable diagnosis, and < 8 indicates a low likelihood of PE.

- Arabic Index of Premature Ejaculation (AIPE): A seven-item questionnaire developed in Saudi Arabia assesses sexual desire, hard erections for sufficient intercourse, time to ejaculation, control, satisfaction of the patient and partner, and anxiety or depression [658]. A cut-off score of 30 (range 7-35) discriminates PE diagnosis best. Severity of PE is classified as severe (score: 7-13), moderate (score: 14-19), mild-to-moderate (score: 20-25) and mild (score: 26-30).

Other questionnaires used to characterise PE and determine treatment effects include the Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP) [649], Index of Premature Ejaculation (IPE) [659] and Male Sexual Health Questionnaire Ejaculatory Dysfunction (MSHQ-EjD) [660]. Currently, their role is optional in everyday clinical practice. The Masturbatory Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (MPEDT) has also been recently proposed [661], due to fact that PE patients report longer IELTs and lesser bother/distress during masturbation than partnered sex [662]; however, further validation studies are required before the routine use of this questionnaire in this population.

6.2.5.3. Physical examination and investigations

Physical examination may be part of the initial assessment of men with PE. It may include a focused examination of the urological, endocrine and neurological systems to identify underlying medical conditions associated with PE or other sexual dysfunctions, such as endocrinopathy, Peyronie’s disease, urethritis or prostatitis. Laboratory or physiological testing should be directed by specific findings from history or physical examination and is not routinely recommended [643].

6.2.5.4. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation of PE

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| A comprehensive medical history and a thorough physical examination can serve as valuable tools for clinicians in identifying the underlying medical factors contributing to PE. | 3 |

| PE can negatively impact self-confidence, strain partner relationships, and potentially lead to emotional distress, anxiety, shame, and depression. | 2a |

| Several questionnaires can be used for the diagnosis of PE (PEDT, AIPE) and for assessing the therapeutic outcomes of PE interventions (PEP). | 2b |

| Although relying on IELT is inadequate for characterizing PE, self-reported IELT proves satisfactory in routine clinical contexts. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Perform the diagnosis and classification of premature ejaculation (PE) based on medical and sexual history, which should include assessment of intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT) (self-estimated), perceived control, distress and interpersonal difficulty due to the ejaculatory dysfunction. | Strong |

| Use patient-reported outcomes in daily clinical practice. | Weak |

| Include physical examination in the initial assessment of PE to identify anatomical abnormalities that may be associated with PE or other sexual dysfunctions, particularly erectile dysfunction. | Strong |

| Do not perform routine laboratory or physiological tests. They should only be directed by specific findings from history or physical examination. | Strong |

6.2.6. Disease management

Before commencing any treatment, it is essential to define the subtype of PE and discuss patient’s expectations thoroughly. Pharmacotherapy must be considered the first-line treatment for patients with lifelong PE, whereas treating the underlying cause (e.g., ED, prostatitis, LUTS, anxiety and hyperthyroidism) must be the initial goal for patients with acquired PE [643]. Various behavioural techniques may be beneficial in treating variable and subjective PE [663]. Psychotherapy can also be considered for PE patients who are uncomfortable with pharmacological therapy or in combination with pharmacological therapy [664,665]. However, there is weak and inconsistent evidence regarding the effectiveness of these psychosexual interventions and their long-term outcomes in PE are unknown [666].

Dapoxetine (30 and 60 mg) is the first on-demand oral pharmacological agent approved for lifelong and acquired PE in many countries, except for the USA [667]. The metered-dose aerosol spray of lidocaine (150 mg/mL) and prilocaine (50 mg/mL) combination is the first topical formulation to be officially approved for on-demand treatment of lifelong PE by the EMA in the European Union [668]. All other medications used in PE are off-label indications [669]. In this context, daily or on-demand use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine and on-demand topical anaesthetic agents have consistently shown efficacy in PE [670-673]. The long-term outcomes of pharmacological treatments are unknown. An evidence-based analysis of all current treatment modalities was performed. Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation are provided, and a treatment algorithm is presented (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1: Management of premature ejaculation

ED = erectile dysfunction; PE = premature ejaculation; IELT = intravaginal ejaculatory latency time; SSRI = selective serotonin receptor inhibitor.

6.2.6.1. Psychological aspects and intervention

Psychosexual interventions, whether behavioural, cognitive, or focused on the couple, are aimed at teaching techniques to control/delay ejaculation, gaining confidence in sexual performance, reducing anxiety, and promoting communication and problem-solving within the couple [663]. Interventions with a focus on sexual education or acceptance may be positive as well [674]. However, psychosexual interventions alone regarding PE lack empirical support. Recent evidence suggests that start-stop exercises, combined with psycho-education and mindfulness techniques improve PE symptoms, as well as PE-associated distress, anxiety and depression [675]. The potential benefits of mindfulness have been reported [676]. Behavioural therapy may be most effective when used to ‘add value’ to medical interventions. Smartphone-delivered psychological intervention, aimed at improving behavioural skills for ejaculatory delay and sexual self-confidence, has positive effects, supporting E-health in the context of PE [677].

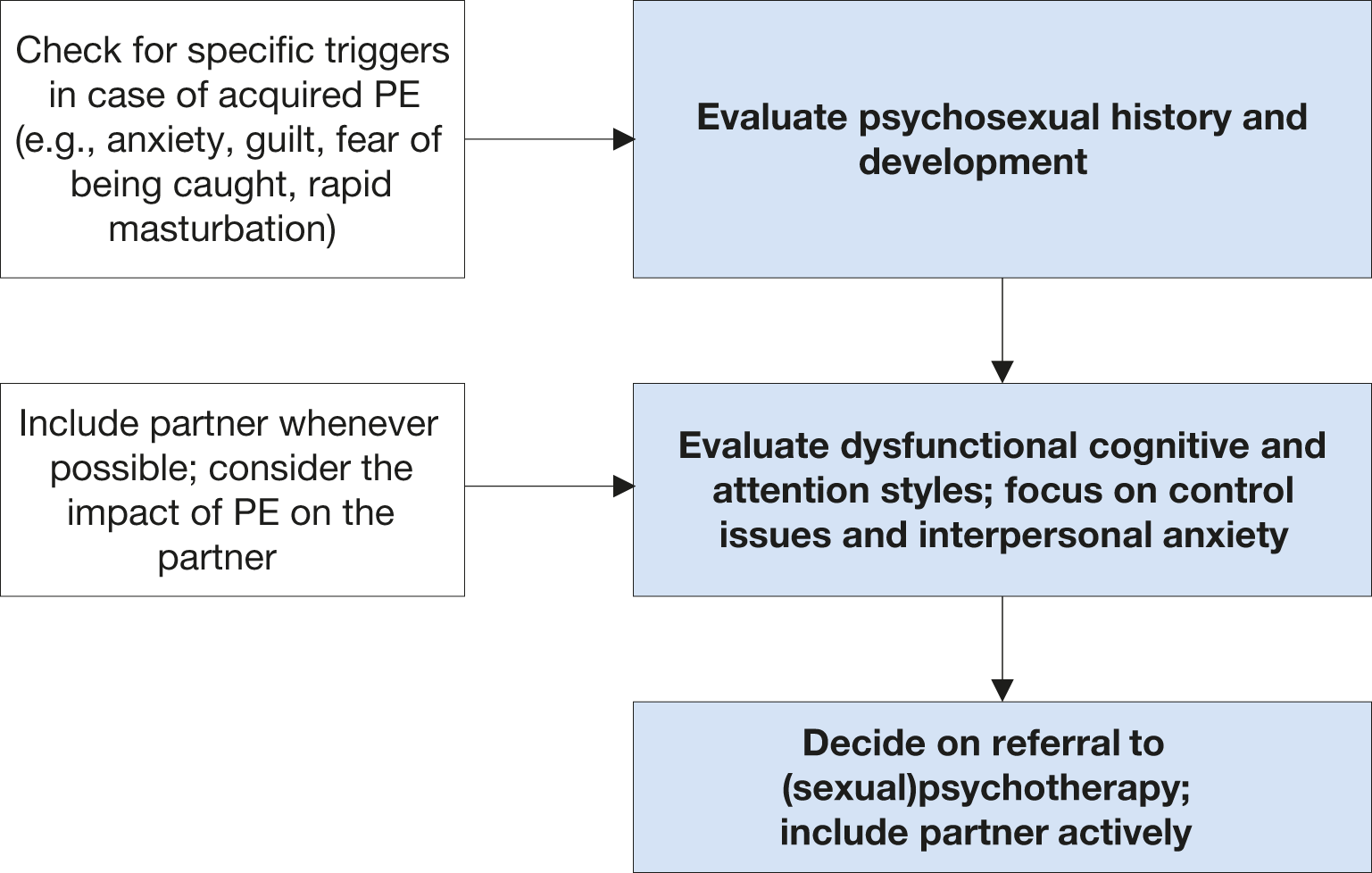

Figure 6.2: Key aspects for psychosexual evaluation

6.2.6.1.1. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the assessment and treatment (psychosexual approach) of PE

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| The incorporation of psychosexual approach, alongside psycho-educational guidance and mindfulness techniques, ameliorate symptoms of PE and alleviate the associated distress, anxiety, and depression. | 2b |

| The combination of psychosexual approaches and pharmacological treatments yields superior outcomes compared to pharmacological interventions alone. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Assess sexual history and psychosexual development. | Strong |

| Assess anxiety, and interpersonal anxiety; focus on control issues. | Strong |

| Include the partner if available; check for the impact of PE on the partner. | Strong |

| Recommendation for treatment (psychosexual approach) | |

| Use behavioural, cognitive and/or couple therapy approaches in combination with pharmacotherapy. Discuss the use of mindfulness exercises. | Weak |

6.2.6.2. Pharmacotherapy

6.2.6.2.1. Dapoxetine

Dapoxetine hydrochloride is a short-acting SSRI with a pharmacokinetic profile suitable for on-demand treatment for PE [678]. It has a rapid Tmax (1.3 hours) and a short half-life (95% clearance rate after 24 hours) [679,680]. It is approved for on-demand treatment of PE in European countries and elsewhere, but not in the USA. Both available doses of dapoxetine (30 mg and 60 mg) have shown 2.5- and 3.0-fold increases, respectively, in IELT overall, rising to 3.4- and 4.3-fold in patients with a baseline average IELT < 30 seconds [681].

In RCTs, dapoxetine, 30 mg or 60 mg 1-2 hours before intercourse, was effective at improving IELT and increasing ejaculatory control, decreasing distress, and increasing satisfaction [681]. Dapoxetine has shown a similar efficacy profile in men with lifelong and acquired PE [681,682]. Treatment-related adverse effects were dose-dependent and included nausea, diarrhoea, thirst, headache and dizziness [682]. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were responsible for study discontinuation in 4% (30 mg) and 10% (60 mg) of subjects [654]. There was no indication of an increased risk of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts and little indication of withdrawal symptoms with abrupt dapoxetine cessation [681,682]. Dapoxetine is safer than formal anti-depressant compounds used for treatment of PE [683].

A low rate (0.1%) of vasovagal syncope was reported in phase 3 studies [684]. According to the summary of product characteristics, vital orthostatic signs (blood pressure and heart rate) must be measured prior to starting dapoxetine, and dose titration must be considered [685]. The EMA assessment report for dapoxetine concluded that the potentially increased risk for syncope had been proven manageable with adequate risk minimisation measures [686]. No cases of syncope were observed in a post-marketing observational study, which identified patients at risk for the orthostatic reaction using the patient’s medical history and orthostatic testing [687].

Many patients and physicians may prefer using dapoxetine in combination with a PDE5I to extend the time until ejaculation and minimise the risk of ED due to dapoxetine treatment. Phase 1 studies of dapoxetine have confirmed that it has no pharmacokinetic interactions with PDE5Is (i.e., tadalafil 20 mg and sildenafil 100 mg) [688]. When dapoxetine is co-administered with PDE5Is, it is well tolerated, with a safety profile consistent with previous phase 3 studies of dapoxetine alone [689]. An RCT, including PE patients without ED, demonstrated that a combination of dapoxetine with sildenafil could significantly improve IELT values and PROs compared with dapoxetine alone or sildenafil alone, with tolerable adverse events [690]. The efficacy and safety of dapoxetine/sildenafil combination tablets for the treatment of PE have also been reported [691].

The discontinuation rates of dapoxetine seem moderate to high [692]. The cumulative discontinuation rates increase over time, reaching 90% at 2 years after initiation of therapy. The reasons for the high discontinuation rate are cost (29.9%), disappointment that PE was not curable and the on-demand nature of the drug (25%), adverse effects (11.6%), perceived poor efficacy (9.8%), a search for other treatment options (5.5%), and unknown (18.3%) [693]. Similarly, it was confirmed that many patients on dapoxetine treatment spontaneously discontinued treatment, while this rate was reported at 50% for other SSRIs and 28.8% for paroxetine, respectively [694]. In a Chinese cohort study, 13.6% of the patients discontinued dapoxetine due to lack of efficacy (62%), adverse effects (24%), and low frequency of sexual intercourse (14%) [695].

6.2.6.2.2. Off-label use of antidepressants

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors are used to treat mood disorders but can delay ejaculation and therefore have been widely used ‘off-label’ for PE since the 1990s [696-698]. Commonly used SSRIs include continuous intake of citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline, all of which have similar efficacy, whereas paroxetine exerts the most substantial ejaculation delay [646,699,700]. A novel 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, GSK958108, significantly delayed ejaculation in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [701].

Clomipramine, the most serotoninergic tricyclic antidepressant, was first reported in 1977 as an effective PE treatment [702,703]. In a recent RCT, on-demand use of clomipramine 15 mg, 2-6 hours before sexual intercourse was found to be associated with IELT fold change and significant improvements in PRO measures in the treatment group as compared with the placebo group (4.66 ± 5.64 vs. 2.80 ± 2.19, P < 0.05) [704,705]. The most commonly reported TEAEs were nausea in 15.7% and dizziness in 4.9% of men, respectively [704,705].

Several meta-analyses suggest SSRIs may increase the geometric mean IELT by 2.6-13.2-fold [706]. Paroxetine is superior to fluoxetine, clomipramine and sertraline [707,708]. Sertraline is superior to fluoxetine, whereas the efficacy of clomipramine is not significantly different from that of fluoxetine and sertraline. Paroxetine was evaluated in doses of 20-40 mg, sertraline 25-200 mg, fluoxetine 10-60 mg and clomipramine 25-50 mg [706-708].

Ejaculation delay may start a few days after drug intake, but it is more evident after one to two weeks as receptor desensitisation requires time to occur. Although efficacy may be maintained for several years, tachyphylaxis (decreasing response to a drug following chronic administration) may occur after six to twelve months [702]. Common TEAEs of SSRIs include fatigue, drowsiness, yawning, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, diarrhoea and perspiration; TEAEs are usually mild and gradually improve after two to three weeks of treatment [702,709]. Decreased libido, anorgasmia, anejaculation and ED have also been reported.

Due to the risk of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, caution is suggested in prescribing SSRIs to young adolescents aged ≤ 18 years with PE, and to men with PE and a comorbid depressive disorder, particularly when associated with suicidal ideation. Patients should be advised to avoid sudden cessation or rapid dose reduction of daily-dosed SSRIs, which may be related to SSRI withdrawal syndrome [654]. Moreover, PE patients trying to conceive should avoid using these medications because of their detrimental effects on sperm cells [710-714].

6.2.6.2.3. Topical anaesthetic agents

The use of local anaesthetics to delay ejaculation is the oldest form of pharmacological therapy for PE [715]. Several trials [582,716,717] support the hypothesis that topical desensitising agents reduce the sensitivity of the glans penis thereby delaying ejaculatory latency, but without adversely affecting the sensation of ejaculation. Meta-analyses have confirmed the efficacy and safety of these agents for the treatment of PE [718]. In a meta-analysis, the efficacy of local anaesthetics was best among the other treatment options including SSRIs, dapoxetine 30 and 60 mg, PDE5Is and tramadol for < 8 weeks of therapy [718].

6.2.6.2.3.1. Lidocaine/prilocaine cream

Lidocaine/prilocaine creams can significantly increase the stopwatch-measured IELT from 1-2 minutes to 6-9 minutes [719,720]. Although no significant TEAEs have been reported, topical anaesthetics are contraindicated in patients or partners with an allergy to any ingredient in the product. These anaesthetic creams/gels may be transferred to the partner, resulting in vaginal numbness. Therefore, patients are advised to use a condom after applying the cream to their penis. Alternatively, the penis can be washed to clean off any residual active compound prior to sexual intercourse. Since these chemicals may be associated with cytotoxic effects on fresh human sperm cells, couples seeking parenthood should not use topical lidocaine/prilocaine-containing substances [721].

6.2.6.2.3.2. Lidocaine/prilocaine spray

The eutectic lidocaine/prilocaine spray is a metered-dose aerosol spray containing purely base forms of lidocaine (150 mg/mL) and prilocaine (50 mg/mL), which has been officially approved by the EMA for the treatment of lifelong PE [722]. Compared to topical creams, the metered-dose spray delivery system has been proved to deposit the drug in a dose-controlled, concentrated film covering the glans penis, maximising neural blockage and minimising the onset of numbness [723], without absorption through the penile shaft skin [724].

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of lidocaine/prilocaine spray in improving both IELT and PROs three sprays administered 5 min before sexual intercourse [725,726]. Published data showed that lidocaine/prilocaine spray increases IELT over time up to 6.3-fold over 3 months, with a month-by-month improvement through the course of the treatment in long-term studies [727]. A low incidence of local TEAEs in both patients and partners has been reported, including genital hypoaesthesia (4.5% and 1.0% in men and female partners, respectively) and ED (4.4%), and vulvovaginal burning sensation (3.9%), but is unlikely to be associated with systemic TEAEs [728,729]. Lidocaine-only sprays are also available and found to be effective in the treatment of PE [730,731].

6.2.6.2.4. Tramadol

Tramadol is a centrally-acting analgesic agent that combines opioid receptor activation and serotonin and noradrenaline re-uptake inhibition. Tramadol is a mild-opioid receptor agonist, but it also displays antagonistic properties on transporters of noradrenaline and 5-HT [732]. This mechanism of action distinguishes tramadol from other opioids, including morphine. Tramadol is readily absorbed after oral administration and has an elimination half-life of 5-7 hours.

Several clinical trials evaluated the efficacy and safety of tramadol ODT (62 and 89 mg) and tramadol HCI in the treatment of PE [733]. Up to 2.5-fold increases in the median IELT have been reported among patients who received on demand tramadol treatment [734,735].

Adverse effects were reported at doses used for analgesic purposes (≤ 400 mg daily) and included constipation, sedation and dry mouth. In May 2009, the US FDA released a warning letter about tramadol’s potential to cause addiction and difficulty in breathing [736]. The tolerability during the twelve-week study period in men with PE was acceptable [737]. Several other studies have also reported that tramadol exhibits a significant dose-related efficacy along with potential adverse effects during the treatment of PE [734,735]. The Guidelines Panel considers tramadol as a potential alternative treatment to established first-line therapeutic options in men with PE; however, it should be clearly outlined that the use of tramadol has to be considered with caution since there is a lack of data on the long-term safety of the compound in this setting.

6.2.6.2.5. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors

Although IELT was not significantly improved, sildenafil increased confidence, the perception of ejaculatory control and overall sexual satisfaction, reduced anxiety and the refractory time to achieve a second erection after ejaculation [738,739]. Several open-label studies have shown that a combination of PDE5Is and SSRIs is superior to SSRI monotherapy, which has also been recently confirmed by a Bayesian network meta-analysis [718,740]:

6.2.6.2.6. Other drugs

In addition to the aforementioned drugs, there is continuous research into other treatment options. Considering the abundant α1a-adrenergic receptors in seminal vesicles and the prostate and the role of the sympathetic system in ejaculation physiology, the efficacy of selective α-blockers in the treatment of PE has been assessed [741-743]. A study demonstrated that wake-promoting agent modafinil may be effective in delaying ejaculation and improving PROMs [744]. Decreasing penile sensitivity with glans penis augmentation using hyaluronic acid for the treatment of PE was initially proposed by Korean researchers in 2004 [745]. Since then, it has gained popularity mainly in Asian countries [746,747]. Randomised controlled studies demonstrated that hyaluronic acid glans injections were safe, with a modest but significant increase in IELT along with improvements in PRO measures [746,747]. No serious TEAEs were reported related to glans penis injections with hyaluronic acid. However, this procedure may result in serious complications, and more safety studies must be conducted before recommending this treatment to PE patients [748]. Selective dorsal neurectomy has also been suggested for the treatment of PE, mainly by Asian researchers [749-755]. However, considering the irreversible nature of these procedures, more safety data are warranted.

Considering the importance of central oxytocin receptors in the ejaculation reflex, several researchers have assessed the efficacy and safety of oxytocin receptor antagonists in the treatment of PE [756]. Epelsiban [757] and cligosiban [758-761] have been found to be safe and mildly effective in delaying ejaculation, but further controlled trials are needed [760,761]. Delayed ejaculation was associated with the use of pregabalin, a new generation of gapapentinoid, as a side-effect. On-demand oral pregabalin 150 mg was found to increase the IELTs of patients 2.45 ± 1.43-fold. Treatment-emergent side effects (blurred vision, dizziness, vomiting) were minimal and did not lead to drug discontinuation [762].

The role of other proposed treatment modalities for the treatment of PE, such as penis-root masturbation [763], vibrator-assisted start-stop exercises [675], transcutaneous functional electric stimulation [764,765], transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation [766], acupuncture [767-769] and practicing yoga [770] need more evidence to be considered in the clinical setting.

6.2.7. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the treatment of PE

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| Pharmacotherapy includes either dapoxetine on-demand (an oral short-acting SSRI) and eutectic lidocaine/prilocaine spray (a topical desensitising agent), which are the only approved treatments for PE, or other off-label antidepressants (daily/on-demand SSRIs and clomipramine). | 1a |

| Both on-demand dapoxetine treatment and daily SSRI treatment improve IELT values significantly. | 1a |

| Both on-demand dapoxetine treatment and daily SSRI treatment have generally tolerable side effects when used for treatment of PE. | 1a |

| Daily/on-demand clomipramine treatments improve IELT values significantly and have generally tolerable side effects when used for treatment of PE. | 1a |

| Cream and spray forms of lidocaine/prilocaine improve IELT values significantly and have a safe profile. | 1b |

| Tramadol is effective in the treatment of PE but the evidence is still inadequate for its long-term safety profile including addiction potential. | 1a |

| Combination of PDE5Is and SSRIs overtakes SSRI monotherapy in effectiveness. | 1a |

| Hyaluronic acid injections are effective in decreasing penile sensitivity. | 2b |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Treat erectile dysfunction (ED), other sexual dysfunction or genitourinary infection (e.g., prostatitis) first. | Strong |

| Use either dapoxetine or the lidocaine/prilocaine spray as first-line treatments for lifelong premature ejaculation (PE). | Strong |

| Use off-label oral treatment with daily selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRIs) or daily/on-demand clomipramine as a viable alternative for second-line treatments. | Strong |

| Use off-label tramadol with caution as a viable on-demand third-line treatment alternative to on-demand/daily antidepressants (SSRIs or clomipramine). | Strong |

| Use PDE5Is alone or in combination with other therapies in patients with PE (without ED). | Strong |

| Use psychological/behavioural therapies in combination with pharmacological treatment in the management of acquired PE. | Weak |

| Use hyaluronic acid injection with caution as a treatment option for PE compared to other more established treatment modalities. | Weak |

| Do not perform dorsal neurectomy as more safety data are warranted. | Weak |

6.3. Delayed Ejaculation (DE)

6.3.1. Definition and classification

The American Psychiatric Association defines delayed ejaculation (DE) as requiring one of two symptoms: marked delay, infrequency or absence of ejaculation on 75-100% of occasions that persists for at least 6 months and causes personal distress [212]. However, in a recent study, while ejaculatory latency and control were significant criteria to differentiate men with DE from those without ejaculatory disorders, bother/distress did not emerge as a significant factor [771]. Similar to PE, there are distinctions among lifelong, acquired and situational DE [212]. A recent study demonstrated that men with lifelong DE are younger, report greater DE symptomatology, less likely have a medical issue or medication that can cause DE and more likely to masturbate for anxiety/distress reduction than for pleasure as compared with men with acquired delayed ejaculation [772]. Although the evidence is limited, the prevalence of lifelong and acquired DE is estimated at around 1% and 4%, respectively [213].

6.3.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

The aetiology of DE can be psychological, organic (e.g., incomplete spinal cord lesion or iatrogenic penile nerve damage), or pharmacological (e.g., SSRIs, antihypertensive drugs, or antipsychotics) [773,774] (Table 6.1). Other factors that may play a role in the aetiology of DE include tactile sensitivity and tissue atrophy [674]. Although low testosterone level has been considered a risk factor in the past [615,775], more contemporary studies have not confirmed any association between ejaculation times and serum testosterone levels [776,777]. Idiosyncratic masturbation and lack of desire for stimuli are also proposed risk factors for DE [778-780].

Table 6.1: Aetiological causes of delayed ejaculation and anejaculation [781-784]

| Aetiological causes of delayed ejaculation and anejaculation | |

| Ageing Men | Degeneration of penile afferent nerves inhibited ejaculation |

| Congenital | Mullerian duct cyst Wolfian duct abnormalities Prune Belly Syndrome Imperforate Anus Genetic abnormalities |

| Anatomic causes | Transurethral resection of prostate Bladder neck incision Circumcision Ejaculatory duct obstruction (can be congenital or acquired) |

| Neurogenic causes | Diabetic autonomic neuropathy Multiple sclerosis Spinal cord injury Radical prostatectomy Proctocolectomy Bilateral sympathectomy Abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy Para-aortic lymphadenectomy |

| Infective/Inflammation | Urethritis Genitourinary tuberculosis Schistosomiasis Prostatitis Orchitis |

| Endocrine | Hypogonadism Hypothyroidism Prolactin disorders Disorders of lipid metabolism |

| Medication | Antihypertensives; thiazide diuretics Alpha-adrenergic blockers Antipsychotics and antidepressants Alcohol Antiandrogens Ganglion blockers |

| Psychological | Anxiety Psychoses Acute psychological distress Relationship distress Psychosexual skill deficit Disconnect between arousal and sexual situations Masturbation style |

6.3.3. Investigation and treatment

Patients should have a full medical and sexual history performed along with a detailed physical examination when evaluating for DE. Understanding the details of the ejaculatory response, sensation, frequency, and sexual activity/techniques; cultural context and history of the disorder; quality of the sexual response cycle (desire, arousal, ejaculation, orgasm, and refractory period); partner’s assessment of the disorder and if the partner suffers from any sexual dysfunction her/himself; and the overall satisfaction of the sexual relationship are all important to garner during history-taking [644]. It is incumbent on the clinician to diagnose medical pathologies that cause or contribute to DE, such as assessing the hormonal milieu, anatomy, and overall medical condition.

6.3.3.1. Psychological aspects and intervention

There is scarce literature on the psychological aspects relating to DE, as well as on empirical evidence regarding psychological treatment efficacy. Studies on psychological aspects have revealed that men with DE show a strong need to control their sexual experiences. Delayed ejaculation is associated with difficulties surrendering to sexual pleasure during sex - i.e., the sense of letting go [785] - which denotes an underlying psychological mechanism influencing the reaching of orgasm [786]. As for psychological treatments, these may include, but are not limited to: increased genital-specific stimulation; sexual education; role-playing on his own and in front of his partner; retraining masturbatory practices; anxiety reduction on ejaculation and performance; and, re-calibrating the mismatch of sexual fantasies with arousal (such as with pornography use and fantasy stimulation compared to reality). Masturbation techniques that are either solo or partnered can be considered practice for the “real performance”, which can eventually result in greater psychosexual arousal and orgasm for both parties [780]. Although masturbation with fantasy can be harmful when not associated with appropriate sexual arousal and context, fantasy can be supportive if it allows blockage of critical thoughts that may prevent orgasm and ejaculation. Techniques geared towards reducing of anxiety are important skills that can help overcome performance anxiety, as this can often interrupt the natural erectile function through orgasmic progression. Referral to a sexual therapist, psychologist or psychiatrist is appropriate and often warranted.

6.3.3.2. Pharmacotherapy

Several pharmacological agents, including cabergoline, bupropion, alpha-1-adrenergic agonists (pseudoephedrine, midodrine, imipramine and ephedrine), buspirone, oxytocin, testosterone, bethanechol, yohimbine, amantadine, cyproheptadine and apomorphine have been used to treat DE with varied success [674]. Unfortunately, there is no FDA or EMA-approved medications to treat DE, as most of the cited research is based on case-cohort studies that were not randomised, blinded, or placebo-controlled. Many drugs have been used as primary treatments and/or antidotes to other medications that can cause DE. A survey of sexual health providers demonstrated an overall treatment success of 40% with most providers commonly using cabergoline, bupropion or oxytocin [787]. However, this survey measured the anecdotal results of practitioners. There was no proven efficacy or superiority of any drug due to a lack of placebo-controlled, randomised, blinded, comparative trials [781]. In addition to pharmacotherapy, penile vibratory stimulation (PVS) is also used as an adjunct therapy for DE [788]. Another study that used combined therapy of midodrine and PVS to increase autonomic stimulation in 158 men with spinal cord injury led to ejaculation in almost 65% of the patients [789].

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| Delayed ejaculation can be caused by several aetiologies including congenital, anatomic, neurogenic, infective, hormonal, drug-related and psychological. | 3 |

| There is not enough evidence to support a definitive treatment for DE. | 3 |

6.4. Anejaculation

6.4.1. Definition and classification

Anejaculation involves the complete absence of antegrade or retrograde ejaculation. It is caused by the failure of semen emission from the seminal vesicles, prostate, and ejaculatory ducts into the urethra [790]. True anejaculation is usually associated with a normal orgasmic sensation and is always associated with central or peripheral nervous system dysfunction or with drugs [791].

6.4.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

Generally, anejaculation shares similar aetiological factors with DE and retrograde ejaculation (Table 6.1).

6.4.3. Investigation and treatment

Drug treatment for anejaculation caused by lymphadenectomy and neuropathy, or psychosexual therapy for anorgasmia, is not effective. In all these cases, and in men who have a spinal cord injury, PVS (i.e., application of a vibrator to the penis) is the first-line therapy. In anejaculation, PVS evokes the ejaculation reflex [792], which requires an intact lumbosacral spinal cord segment. If the quality of semen is poor or ejaculation is retrograde, the couple may enter an in vitro fertilisation program whenever fathering is desired. If PVS has failed, electro-ejaculation can be the therapy of choice [793]. Other sperm-retrieval techniques may be used when electro-ejaculation fails or cannot be carried out [794]. Anejaculation following either retroperitoneal surgery for testicular cancer or total mesorectal excision can be prevented using unilateral lymphadenectomy or autonomic nerve preservation [795], respectively.

6.5. Painful Ejaculation

6.5.1. Definition and classification

Painful ejaculation is a condition in which a patient feels mild discomfort to severe pain during or after ejaculation. The pain can involve the penis, scrotum, and perineum [796].

6.5.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

Many medical conditions can result in painful ejaculation, but it can also be an idiopathic problem. Initial reports demonstrated possible associations of painful ejaculation with calculi in the seminal vesicles [797], sexual neurasthenia [798], sexually transmitted diseases (STIs) [796,799], inflammation of the prostate [233,800], PCa [801,802], BPH [231], prostate surgery [803,804], pelvic radiation [805], herniorrhaphy [806] and antidepressants [807-809]. Further case reports have suggested that mercury toxicity or Ciguatera toxin fish poisoning may also result in painful ejaculation [810,811]. Psychological issues may also be the cause of painful ejaculation, especially if the patient does not experience this problem during masturbation [812].

6.5.3. Investigation and treatment

Treating painful ejaculation must be tailored to the underlying cause if detected. Psychotherapy or relationship counselling, withdrawal of suspected agents (drugs, toxins, or radiation) [807,808,813] or the prescription of appropriate medical treatment (antibiotics, α-blockers or anti-inflammatory agents) may ameliorate painful ejaculation. Behavioural therapy, muscle relaxants, antidepressant treatment, anticonvulsant drugs and/or opioids, and pelvic floor exercises, may be implemented if no underlying cause can be identified [814,815].

6.5.3.1. Surgical intervention

If medical treatments fail, surgical operations such as TURP, transurethral resection of the ejaculatory duct (TURED) and neurolysis of the pudendal nerve have been suggested [816,817]. However, there is no strong supporting evidence that surgical therapy improves painful ejaculation: therefore, it must be used with caution.

6.6. Retrograde ejaculation

6.6.1. Definition and classification

Retrograde ejaculation is the total, or sometimes partial, absence of antegrade ejaculation, due to semen passing backwards through the bladder neck into the bladder. Patients may experience a normal or decreased orgasmic sensation. The causes of retrograde ejaculation can be divided into neurogenic, pharmacological, urethral, or bladder neck incompetence [796].

6.6.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

The process of ejaculation requires complex co-ordination and interplay between the epididymis, vas deferens, prostate, seminal vesicles, bladder neck and bulbourethral glands [818]. Upon ejaculation, sperm are rapidly conveyed along the vas deferens and into the urethra via the ejaculatory ducts. From there, the semen progresses in an antegrade fashion, partly maintained by coaptation of the bladder neck and rhythmic contractions of the periurethral muscles, co-ordinated by a centrally mediated reflex [818]. Closure of the bladder neck and seminal emission is initiated via the sympathetic nervous system from the lumbar sympathetic ganglia and subsequently hypogastric nerve. Prostatic and seminal vesicle secretion, as well as contraction of the bulbo-cavernosal, ischio-cavernosal and pelvic floor muscles are initiated by the S2-4 parasympathetic nervous system via the pelvic nerve [818].

Any factor that disrupts this reflex and inhibits contraction of the bladder neck (internal vesical sphincter) may lead to retrograde passage of semen into the bladder. These can be broadly categorised as pharmacological, neurogenic, anatomic and endocrinal causes of retrograde ejaculation (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2: Aetiology of retrograde ejaculation [796]

| Neurogenic | Spinal cord injury Cauda equina lesions Multiple sclerosis Autonomic neuropathy Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy Sympathectomy or aortoiliac surgery Prostate, colorectal and anal surgery Parkinson´s disease Diabetes mellitus Psychological/behavioural |

| Urethral | Ectopic ureterocele Urethral stricture Urethral valves or verumontaneum hyperplasia Congenital dopamine β-hydroxylase deficiency |

| Pharmacological | Antihypertensives, thiazide diuretics α-1-Adrenoceptor antagonists Antipsychotics and antidepressants |

| Endocrine | Hypothyroidism Hypogonadism Hyperprolactinaemia |

| Bladder neck incompetence | Congenital defects/dysfunction of hemitrigone Bladder neck resection (transurethral resection of the prostate) Prostatectomy |

6.6.3. Disease management

6.6.3.1. Pharmacological

Sympathomimetics stimulate the release of noradrenaline and activate α- and β-adrenergic receptors, resulting in closure of the internal urethral sphincter, restoring the antegrade flow of semen. The most common sympathomimetics are synephrine, pseudoephedrine hydrochloride, ephedrine, phenylpropanolamine and midodrine [819]. Unfortunately, as time progresses, their effect diminishes [820]. Many studies published about the efficacy of sympathomimetics in the treatment of retrograde ejaculation suffer from small sample size, with some represented by case reports.

An RCT randomised patients to receive one of four α-adrenergic agents (dextroamphetamine, ephedrine, phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine) with or without histamine. The patients suffered from failure of ejaculation following retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. They found that four days of treatment prior to ejaculation was the most effective and that all the adrenergic agonists restored antegrade ejaculation [819]. In a systematic review, the efficacy of this group of medications was found to be 28% [216]. The adverse effects of sympathomimetics include dryness of mucous membranes and hypertension.

The use of antimuscarinics has been described, including brompheniramine maleate and imipramine, as well as in combination with sympathomimetics. The calculated efficacy of antimuscarinics alone or in combination with sympathomimetics is 22% and 39%, respectively [216]. Combination therapy appears to be more effective, although statistical analysis is not yet possible due to the small sample sizes.

6.6.3.2. Management of infertility

Infertility has been the major concern of patients with retrograde ejaculation. Beyond standard sperm-retrieval techniques, such as testicular sperm aspiration/extraction (TESA/TESE), three different methods of sperm acquisition have been identified for managing infertility in patients with retrograde ejaculation. These include: i) centrifugation and resuspension of post-ejaculatory urine specimens; ii) the Hotchkiss (or modified Hotchkiss) technique; and, iii) ejaculation on a full bladder.

- Centrifugation and resuspension. In order to improve the ambient conditions for the sperm, the patient is asked to increase their fluid intake or take sodium bicarbonate to dilute or alkalise the urine, respectively. Afterwards, a post-orgasmic urine sample is collected by introducing a catheter or spontaneous voiding. This sample is then centrifuged and suspended in a medium. The types of suspension fluids are heterogeneous and can include bovine serum albumin, human serum albumin, Earle’s/Hank’s balanced salt solution and the patient’s urine. The resultant modified sperm mixture can then be used in assisted reproductive techniques. A systematic review of studies in couples in which male partner had retrograde ejaculation found a 15% pregnancy rate per cycle (0-100%) [216].

- Hotchkiss method. The Hotchkiss method involves emptying the bladder prior to ejaculation, using a catheter, and then washing out and instilling a small quantity of Lactated Ringers to improve the ambient condition of the bladder. The patient then ejaculates, and semen is retrieved by catheterisation or voiding [821]. Modified Hotchkiss methods involve variance in the instillation medium. Pregnancy rates were 24% per cycle (0-100%) [216].

- Ejaculation on a full bladder. The patient is encouraged to ejaculate on a full bladder and semen is suspended in Baker’s Buffer. The pregnancy rate in the two studies, which included only five patients, have described results using this technique [822,823].

6.7. Anorgasmia

6.7.1. Definition and classification

Anorgasmia is the perceived absence of orgasm and can give rise to anejaculation. Regardless of the presence of ejaculation, anorgasmia can be a lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary) disorder [213].

6.7.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

Primary anorgasmia starts from a man’s first sexual intercourse and lasts throughout his life, while secondary anorgasmia patients should have a normal period before the problem starts [824]. Substance abuse, obesity and some non-specific psychological aspects, such as anxiety and fear, are considered risk factors for anorgasmia. Only a few studies have described anorgasmia alone and generally, it has been considered a symptom linked to ejaculatory disorders, especially with DE, and therefore, they are believed to share the same risk factors. However, psychological factors are considered to be responsible for 90% of anorgasmia problems [825]. The causes of delayed orgasm and anorgasmia are shown in Table 6.3 [824].

Table 6.3: Causes of delayed orgasm and anorgasmia [824]

| Causes of delayed orgasm and anorgasmia |

| Endocrine: Testosterone deficiency; and Hypothyroidism |

| Medications: Antidepressants; Antipsychotics; and Opiods |

| Psychosexual causes |

| Hyperstimulation |

| Penile sensation loss |

6.7.3. Disease management

The psychological/behavioural strategies for anorgasmia are similar to those for DE. The patient and his partner should be examined physically and psychosexually in detail, including determining the onset of anorgasmia, medication and disease history, penile sensitivity and psychological issues. Adjunctive laboratory tests can also be used to rule out organic causes, such as testosterone, prolactin and TSH levels. Patients who have loss of penile sensitivity require further investigations [824].

6.7.3.1. Psychological/behavioural strategies

Lifestyle changes can be recommended to affected individuals, including changing masturbation style, taking steps to improve intimacy, and decreasing alcohol consumption. Several psychotherapy techniques or their combinations have been offered, including alterations in arousal methods, reduction of sexual anxiety, role-playing an exaggerated orgasm and increased genital stimulation [786,826]. However, it is difficult to determine the success rates from the literature.

6.7.3.2. Pharmacotherapy

Several drugs have been reported to reverse anorgasmia, including cyproheptadine, yohimbine, buspirone, amantadine and oxytocin [827-832]. However, these reports are generally from case-cohort studies and drugs have limited efficacy and significant adverse effect profiles. Therefore, current evidence is not strong enough to recommend drugs to treat anorgasmia.

6.7.3.3. Management of infertility

If patients fail the treatment methods mentioned above, penile vibratory stimulation, electro-ejaculation or TESE are options for sperm retrieval in anorgasmia cases [824].

6.8. Haemospermia

6.8.1. Definition and classification

Haemospermia is defined as the appearance of blood in the ejaculate. Although it is often regarded as a symptom of minor significance, blood in the ejaculate causes anxiety in many men and may indicate underlying pathology [236].

6.8.2. Pathophysiology and risk factors

Several causes of haemospermia have been acknowledged and can be classified into the following sub-categories; idiopathic, congenital malformations, inflammatory conditions, obstruction, malignancies, vascular abnormalities, iatrogenic/trauma and systemic causes (Table 6.4) [833].

Table 6.4: Pathology associated with haemospermia

| Category | Causes |

| Congenital | Seminal vesicle (SV) or ejaculatory duct cysts |

| Inflammatory | Urethritis, prostatitis, epididymitis, tuberculosis, CMV, HIV, Schistosomiasis, hydatid, condyloma of urethra and meatus, urinary tract infections |

| Obstruction | Prostatic, SV and ejaculatory duct calculi, post-inflammatory, seminal vesicle diverticula/cyst, urethral stricture, utricle cyst, BPH |

| Tumours | Prostate, bladder, SV, urethra, testis, epididymis, melanoma |

| Vascular | Prostatic varices, prostatic telangiectasia, haemangioma, posterior urethral veins, excessive sex or masturbation |

| Trauma/ iatrogenic | Perineum, testis, instrumentation, post-haemorrhoid injection, prostate biopsy, vaso-venous fistula |

| Systemic | Hypertension, haemophilia, purpura, scurvy, bleeding disorders, chronic liver disease, renovascular disease, leukaemia, lymphoma, cirrhosis, amyloidosis |

| Idiopathic | - |

The risk of any malignancy in patients presenting with haemospermia is approximately 3.5% (0-13.1%) [835,837]. In a study in which 342 patients with haemospermia were included, the most relevant aetiology for haemospermia was inflammation/infection (49.4%) while genitourinary cancers (i.e., prostate and testis) only accounted for 3.2% of the cases [838].

6.8.3. Investigations

As with other clinical conditions, a systematic clinical history and assessment is undertaken to help identify the cause of haemospermia. Although the differential diagnosis is extensive, most cases are caused by infections or other inflammatory processes [236].

The basic examination of haemospermia should start with a thorough symptom-specific and systemic clinical history. The first step is to understand if the patient has true haemospermia. Pseudo-haemospermia may occur as a consequence of haematuria or even suction of a partner’s blood into the urethra during copulation [796,839,840]. A sexual history should be taken to identify those whose haemospermia may be a consequence of a STI. Recent foreign travel to areas affected by schistosomiasis or tuberculosis should also be considered. The possibility of co-existing systemic diseases such as hypertension, liver disease and coagulopathy should be investigated along with systemic features of malignancy such as weight loss, loss of appetite or bone pain. Examination of the patient should also include measurement of blood pressure, as there have been several case reports suggesting an association between uncontrolled hypertension and haemospermia [841,842].

Most authors who propose an investigative baseline agree on the initial diagnostic tests, but there is no consensus in this regard [833,834,837,839]. Urinalysis should be performed along with sending the urine for culture and sensitivity testing, as well as microscopy. If tuberculosis or schistosomiasis is the suspected cause, the semen or prostatic secretions should be sent for analysis. A full sexually-transmitted disease screen, including first-void urine as well as serum and genitourinary samples, should be tested for Chlamydia, Ureaplasma and Herpes Simplex virus. Using this strategy, it may be possible to find an infectious agent among cases that would have been labelled as idiopathic haemospermia [843].

Serum PSA should be taken in men aged > 40 years who have been appropriately counselled [237]. Blood work, including a full blood count, liver function tests, and a clotting screen should be taken to identify systemic diseases. The question of whether further investigation is warranted depends on clinician judgment, patient age and an assessment of risk factors [833]. Digital rectal examination should also be performed, and the meatus re-examined after DRE for bloody discharge [844]. Detection of a palpable nodule in the prostate is important because an association between haemospermia and PCa has been postulated, although not completely proven.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is being increasingly used as a definitive means to investigate haemospermia. The multiplanar ability of MRI to accurately represent structural changes in the prostate, seminal vesicles, ampulla of vas deferens, and ejaculatory ducts has enabled the technique to be particularly useful in determining the origin of midline or paramedian prostatic cysts and in determining optimal surgical management [845]. The addition of an endorectal coil can improve diagnostic accuracy for identifying the site and possible causes of haemorrhage [846].

Cystoscopy has been included in most suggested investigative protocols in patients with high-risk features (patients who are refractory to conservative treatment and who have persistent haemospermia). It can provide valuable information as it allows direct visualisation of the main structures in the urinary tract that can be attributed to causes of haemospermia, such as polyps, urethritis, prostatic cysts, foreign bodies, calcifications and vascular abnormalities [847,848].

With the advancement of optics, the ability to create ureteroscopes of diameters small enough to allow insertion into the ejaculatory duct and seminal vesicles has been made possible [849]. In a prospective study, 106 patients with prolonged haemospermia underwent transrectal US and seminal vesiculoscopy. With both methods combined, the diagnosis was made in 87.7% of patients. When compared head-to-head, the diagnostic yield for TRUS vs. seminal vesiculoscopy was 45.3% and 74.5%, respectively (P < 0.001) [850].

Melanospermia is a consequence of malignant melanoma involving the genitourinary tract and is a rare condition that has been described in two case reports [851,852]. Chromatography of the semen sample can be used to distinguish the two by identifying the presence of melanin if needed.

6.8.4. Disease management

Conservative management is generally the primary treatment option when the patients are aged < 40 years and have a single episode of haemospermia. The primary goal of treatment is to exclude malignant conditions like prostate and bladder cancer and treat any other underlying cause. If no pathology is found, then the patient can be reassured [236,833].

Middle-aged patients with recurrent haemospermia warrant more aggressive intervention. Appropriate antibiotic therapy should be given to patients who have urogenital infections or STIs. Urethral or prostate varices or angiodyplastic vessels can be fulgurated, whereas cysts, either of the seminal vesicles or prostatic urethra, can be aspirated transrectally [236]. Ejaculatory duct obstruction is managed by transurethral incision at the duct opening [853,854]. Systemic conditions should be treated appropriately [837,840,855,856].

Defining a management algorithm for haemospermia is based on the patient age and degree of haemospermia. Patients often find blood in the ejaculate alarming, and investigations should be aimed at excluding a serious, despite infrequent, underlying cause (e.g., cancer), while at the same time preventing over-investigation and alleviating patient anxiety. The literature describes a multitude of causes for haemospermia, although many of these are not commonly found after investigation. However, men may be stratified into higher-risk groups according to several factors including: age > 40 years, recurrent or persistent haemospermia, the actual risk for PCa (e.g., positive family history), and concurrent haematuria. Based upon the literature, a management algorithm is proposed (Figure 6.3) [837,840,855,856].

Figure 6.3: Management of haemospermia [837,840,855,856]

STI = Sexually transmitted infections; PSA = Prostate specific antigen; DRE = Digital rectal examination;US = Ultrasonography; TRUS = Transrectal ultrasonography; MRI = Magnetic resonance imaging.

6.8.5. Summary of evidence and recommendations for the investigation and management of haemospermia

| Summary of evidence | LE |

| While haemospermia has traditionally been attributed to benign causes, it is a potential indicator warranting thorough diagnostic evaluation and, if necessary, targeted treatment. | 3 |

| The principal objective of treatment is to rule out malignancies, while addressing any other underlying causes as well. | 3 |

| Recommendations | Strength rating |

| Perform a full medical and sexual history with detailed physical examination. | Strong |

| Use risk-stratification system to manage the disease systematically. | Weak |